To give this story historic context the events took place one year and 51 days before the death of Queen Victoria and 52 days after the start of the 2nd Boer War in South Africa.

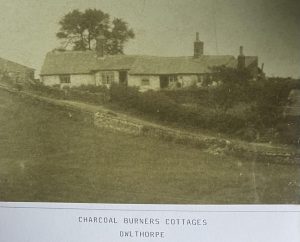

The story begins on Owlthorpe Hill shortly before Christmas in 1899.

The lonely little hamlet of Owlthorpe, is located about three-quarters of a mile from Mosborough, which many will be aware was part of the parish of Eckington in North East Derbyshire.

It consisted of four houses, two detached, and two adjoining each other.

Charcoal Hunters Cottages Owlthorpe Map highlighted in red by

(donated by T L Platts family). John Rotherham of possibly the Bird’s home.

In the first house reached on the road from Mosborough lived George Staniforth and his wife Emma Jane who had married the previous year on June 27.

The next house was the one which was occupied by Henry Bird a labourer, and a kind of small market gardener, aged about 50 and his wife Emily.

Emma Jane Staniforth was the daughter of Mr. & Mrs. Bird.

Further still were the two cottages in one of which lived Christopher Taylor a miner, his wife Ann and their seven children. Taylor was described as a short, slightly built man, about 35 years of age. He was an intelligent looking man, with a type of face frequently found amongst miners.

He was a Lancashire man, hailing from Wigan, but he has lived in the Owlthorpe district about seven years having worked during the greater part of that time at the Holbrook Collieries.

There had been no longstanding quarrel between the parties; they had according to all accounts lived amicably together as neighbours.

Saturday, December 2, 1899 – Owlthorpe Hill

Henry Bird was at home all that Saturday and first saw Christopher Taylor about eleven o’clock in the morning.

He was then sitting at the door of his house with a gun in his hand, looking for some of those birds that came for berries.This gun was well known, Taylor having apparently been fond of it.

Taylor’s garden faced Bird’s house, and was about 70 yards distant.

Bird was about 20 yards from Taylor who did not speak to him or take any notice of him. Nor did Bird speak to Taylor.

Taylor was a man with a reputation for being quarrelsome, and he seems to have done no work on Saturday, but to have spent some time in drinking.

Early in the evening Christopher Taylor, with his wife, had been in the British Oak public house, half a mile away from his house, and the evidence went to show that he was drunk at the time.

Taylor returned home more or less excited with drink

It appears that Taylor felt aggrieved about a rumour which had spread, to the effect that he was in debt. He believed the report to have originated with his neighbour Bird and this was the cause of his vindictive spirit.

As the short day darkened to its close the sun set at ten minutes to four, Henry Bird and his wife had gone to the house of their son-in-law, George Staniforth.

The only people in the house were George Staniforth sitting in a chair, and Henry Bird and his wife. Emma Staniforth, George’s wife had gone to Mosborough, and had asked her mother to make some pastry for her.

Henry Bird was sitting by the fire looking at the war pictures – the Staniforth’s had gotten a few – and George used to read to his father-in-law at night.

Mrs. Bird had started to mix the pastry for her daughter.

It was at that time, about a quarter to eight, when he heard Taylor and his wife coming up the lane shouting, gauping, and making ever such a noise.

Bird heard his name called over a time or two and after about 5 minutes he opened the door and saw Taylor leaning against the wall alongside Bird’s garden.

He also saw a woman’s form in the road.

Taylor kept on gauping “I will blow you (expletive) head off,” and “I will set your (expletive) house on fire.” Taylor’s wife tried to get him to go home.

Bird stood there and said nothing for a while.

Then Bird said to Taylor, “Here, do you know what you are talking about?” It was (expletive) every word almost he spoke. He could not open his mouth without it.

Bird then said, “If you don’t mine what you say, I will take you somewhere else.”

Taylor was still for about a minute, he then took off his coat and got over the garden wall in his shirt sleeves.

Once in Bird’s garden he began doing wanton damage to the plants, and threatening him and he came across the garden to within two yards of Bird and challenged him to fight.

Bird declined, where upon Taylor walked back into Bird’s garden and continued trampling some plants down.

Bird told him he would have to pay for the damage committed.

Bird came up and told him he had caught him fairly, and that Taylor would hear more about it.

Bird puts himself in an attitude as if he was going to strike Taylor.

Taylor’s wife came running down to the door stone to me, and said, “Take no notice of him, Mr. Bird.”Mrs. Taylor kept on saying to her husband “Come on ”

Bird said, “I don’t, but see how he has trampled on my flower plants. He will have to pay for trampling them down like that.”

Taylor did not say anything and Bird turned round and went into the door place.

George Staniforth came to the door and Bird told Taylor. “You must mind what you are talking about I have a witness here.”

Within a moment there was some more shouting and gauping, and Mrs. Bird was stood at the end of the table, near the door, working, and Taylor was shouting and gauping.

Taylor in the garden shouted out, “Bring a leet; I’ve lost me (expletive) jacket,” and this he repeated several times.

Mrs. Bird says, “I will go and fetch you our stable lamp, and look for it, or else he will be trampling all the plants down.”

Bird said to her, “Never mind,” but she took the key, brought the lamp and lighted it, and went out into the gardening, but Bird did not go out of doors himself.

Shortly afterwards Mrs. Bird returned to say that the jacket was found.

Taylor went away, and returned with a loaded gun

Mrs. Bird went to take the lamp home, but almost immediately she rushed back with the lantern and she immediately retreated within her daughter’s house, and in a great fright said, “He’s coming with a gun and says he is bound to blow your (expletive) head off.” She closed and bolted the door.

She had just slotted the bolt and stood for a moment with her back to the door.

Bird heard Taylor run across the garden, but he did not really hear his footsteps until he caught his foot against a stone

Not more than a second after Taylor said, “I’ll blow your (expletive) head of.”

Taylor had no sooner said the words then finding the door had just been shut in his face, put the muzzle to one of the panels, and fired through it.

The shot made a clean hole through the door.

On the other side of the door was Mrs. Bird who received the full charge at the back of the head, the spinal cord was shattered, and she died instantly.

Bird saw the smoke pass his wife’s ear as she stood up against the door, he was not half a yard off her, and also saw the hole in the door made by the bullet.

Mrs. Bird was wounded at the back of her neck and her hair was full of chips of splintered wood like dried chaff and ground up.

As soon as ever the shot struck her she began to settle down, and Bird went to steady her, and put his hand on the back of her head right on the wound from which she was bleeding profusely and said, “Oh, dear, she’s dead! She’s dead!”

She was dead that instant the gun went off; it was instant death.

Bird screamed out, and Taylor took his hook across the garden and off home.

She bled terribly, and subsequent examination confirmed that death must have been almost instantaneous.

It is not supposed that Taylor knew where the unfortunate woman was when he fired, but his conduct after the event was such as to put the worst colour upon his intentions.

As soon as Bird could put the deceased down he went out of the door and rushed off in the direction of Mosborough to fetch his daughter and a policeman and give the alarm. He could not see anything of Taylor.

Staniforth was left in the room with the murdered woman, he having been the only other person present.

It appears that during Bird’s absence Taylor did not interfere with Staniforth, but went back to his own house.

Taylor’s passion still held the upper hand.

Having returned to his house, he again loaded the barrel he had fired, and paced the roads around, threatening one and all, and for some time completely terrorised the whole neighbourhood.

Edmond Jowett, was a farmer of Mosborough Moor, that lived about 400 yards from Owlthorpe.

About 8:20 p.m. that Saturday he was in the yard when he heard two voices as though quarrelling, which was followed by a gunshot.

Afterwards he heard someone running on the road, and going out he met Henry Bird who was crying.

When asked what the matter was, Bird said, “Chris Taylor’s shot my wife.”

Jowett drove to Mosborough and reported the matter to P.C. Tom Adlington, who was stationed at Mosborough, returned with Jowett in the cart to Owlthorpe.

P.C. Adlington, based on information received from Jowett, went to the house of George Staniforth, and saw the body of Emily Bird lying dead on the floor of the house with a wound in her neck.

The hole in the door was about the size of a four shilling piece outside, but inside it was larger, the shot having spread.

P.C. Adlington, was unable to secure his man, owing to the night being pitch dark and want of adequate assistance.

He at once sent a messenger to Eckington to Police- Superintendent Benjamin Thomas Talbot, in charge of the Eckington division, and then kept watch on Taylor’s house.

Whilst he was thus on guard Taylor came out into the garden.

P.C. Adlington then went towards Taylor’s house with Mr. Jowett, and by a light from the house they saw him marching up and down the garden with the gun in one hand and a large knife in the other.

He was threatening to put lead and steel into the first person who approached him.

They bent down under the garden hedge, and Taylor shouted, “I can hear the (expletive) sticks cracking. Who the (expletive) is there? If you don’t (expletive) come out I’ll put some (expletive) lead into you if you don’t.”

He followed them, and they went farther down the lane and when they got at the back of a wall by the side of Bird’s gateway, with Jowett standing on one side of the gateway, and the Police Constable on the other.

Taylor came to within a yard of where they were, he was heard to threaten that he would kill any policeman who came near him and said, “Come out. I don’t care who the (expletive) you are. I shall put some shot into you or some cold steel.”

His threats were not confined to the police; in fact, he terrorised the whole neighbourhood, his actions were those of a madman.

Taylor went up the lane again and went into his house and they followed him, getting behind a wall that was near the gable end of a neighbour’s house.

He came out in a few minutes, and said, “I’ll burn all the (expletive) lot up. I’ll have a bonfire with oil and paraffin that will (expletive) well shift owt.”, and then added, “see how it blazes,” but witness could not see anything burning.

At about twenty minutes past nine Superintendant Talbot, who had made all haste, reached the place in a conveyance in company with Police-sergeant Hughes and Police-constable Roland.

They went into Staniforth’s house and found the woman lying dead on the floor in a large pool of blood, which had saturated her clothing, and was running out over the doorstep.

Nothing could be done there, and Superintendant Talbot turned his attention to arresting the murderer, a task which involved the utmost peril, for he could be heard using threatening language in the house.

Superintendent Talbot knew the sort of man he had to deal with, and every possible precaution was observed, he made his arrangements accordingly.

P.C. Adlington went up to Taylor’s house again with the Superintendent and Sergeant Hughes.

Taylor put his head through a window, and said, “Let that big fat-bellied Sergeant come: I know he hasn’t much stomach.

The Superintendentsent P.C. Adlington to borrow a gun from Mr. Staniforth.

He stationed Constable Roland to guard the window at the back of the prisoner’s house.

Superintendant Talbot went up to the door of the cottage, which is a structure of only one storey.

The door was found to be locked, and Superintendant Talbot ordered it to be broken in.

Sergeant Hughes ran at the door with his foot, and the door flew open

At the same time the Superintendent fired the gun into the air outside. The gun was discharged in order to let Taylor see that the police had firearms

Superintendent Talbot rushed into the house, followed close behind by Constable Adlington and Sergeant Hughes, and finding that their man was not in the front or living room, they rushed into the bedroom, which adjoins it on the same level.

They saw Taylor sitting on a bed in a room on the right hand side going in with a large single-bladed, spring-backed knife open and grasped in his right hand and a gun in his left hand that was fully loaded, capped, and cocked.

If it was his intention to fire, as seems probable, it was happily frustrated, for Superintendant Talbot and the other officers had grappled with him, and disarmed him in a moment.

The Superintendant led the way into the room, and wrestled the gun from him; the sergeant sprung on him and held him back on the bed, whilst P.C. Adlington took the knife, a formidable looking weapon, from him.

Some of Taylor’s seven children were in the house when their father was arrested.

They then took himinto custody; the handcuffs were quickly affixed to Taylor restraining him between P.C. Adlington and the Superintendent, and went down to Staniforth’s house where the body was.

When taken to the scene of the tragedy Taylor evinced no signs of sorrow or compunction for his crime, but rather gloried in his act, and threatened the husband of his victim with further violence if he had the opportunity.

There the Superintendent charged Taylor with “the wilful murder, killing and slaying Emma Bird by shooting her with a gun.” and will be brought up on that charge at Eckington Petty Sessions.

The prisoner Taylor was then marched off to the police station at Eckington, were he was locked up.

Even after his arrest, Taylor used language of a violent and threatening kind; and abused the police in the coarsest language.

He said “You can do what the (expletive) fire you like. They can but hang me, can they? If I live to get out again I will “do for” Bird at the earliest opportunity,”

They rather roughly handled Taylor, but not more than was necessary.

The gun which was an old pattern muzzle-loading double-barrelled gun and both barrels were found to be loaded with ordinary shot.

Both barrels were at full cock when the Superintendent took it away from Taylor, but he did not see the knife until it was taken by force from his possession.

The gun that was borrowed from Staniforth was for the purpose of deterring Taylor from injuring them, and not for the purpose of injuring him.

Taylor was again charged at the Police Office at Eckington, and he said, “It was done in a quarrel. I fired through the door. I fired the gun off not with the intention of doing any harm.”

Shortly after the arrest Dr. West Jones, a surgeon of Eckington, had been summoned to Owlthorpe, he went into Staniforth’s house, and made an examination of the deceased woman’s body.

He found the body of deceased lying on the floor in a pool of blood, quite dead.

The front of her clothing was saturated with blood, and there was a wound on the right hand side of the neck at the back.

It was a jagged wound, and one that would have been caused by a gun-shot.

Sunday, December 3, 1899 – Post-Mortem

Dr. Jones, of Eckington, and his assistant held a post-mortem examination of the body, on Sunday afternoon preparatory to the inquest, to be held on Tuesday morning.

Above the right shoulder-blade were some slight wounds, evidently caused by shot.

In the jagged wound he found a large number of fragments of bone.

He removed the skull cap, and found the base of the skull intact, but on passing the finger through the neck it was evident that the two upper vertebrae were shattered all to pieces, and the spinal cord cut through close to its junction with the brain.

Death must have taken place instantaneously.

Monday, December 4, 1899 – Eckington Police Court

The Tragic death of Emily Bird, at Owlthorpe, had caused a profound sensation in the district of Eckington, and the incidents of the terrible affair were the chief topics of conversation during Sunday.

At the Eckington Petty Sessions Taylor was brought up before Ald. J.F. Swallow and Major L.B. Bowdon, charged with the wilful murder of Emily Bird.

Superintendent Talbot asked for a remand for a week.

Much sympathy is expressed for Bird, the dead woman’s husband, who is very much affected by his wife’s end.

On the other hand, Taylor, the man who fired the gun which caused the woman’s death, takes the whole thing with astonishing coolness; during the proceedings at the Police Court, he maintained a most unconcerned air.

The excitement created by the event was evinced in the presence of a large crowed in front of the Courthouse.

Only those having business before the magistrates were admitted, however, and in consequence, the Court bore its usual appearance.

Neither the police nor the prisoner were legally represented, and Superintendent Talbot was the only person to give evidence.

Superintendent Talbot’s testimony was chiefly an account of the method adopted to secure Taylor, who had locked himself into his house, and armed with a gun and a knife, was prepared to defy the world.

He said the prisoner was taken into custody on Saturday night, and was charged with feloniously, wilfully, and with malice aforethought killing Emily Bird.

About nine o’clock that night he (the superintendent) received information that a murder had been committed at Owlthorpe,

He went to the house of George Staniforth, of Owlthorpe, and there saw the body of the dead woman.

It was in a terrible state, almost covered with blood.

There was a large pool of blood on the floor of the outer living room near the outer door.

On inspecting the body he found a large wound on the back of the neck.

The woman was quite dead.

In the outer door there was a hole made by a gunshot about 1¼ inches in diameter.

With Sergeant Hughes and Constables Adlington and Roland witness searched the prisoner’s premises, and he heard a man’s voice shouting.

Having been advised to take precautions witness got a gun.

Roland was sent to the back of the house.

Witness fired into the air, and as soon as he did so, the sergeant and Adlington burst the door open and rushed in, witness following.

Prisoner, who had a gun and a knife, was at once collared, and these weapons were taken from him.

He was then taken to Bird’s house, and after a caution was charged with murder of Emily Bird.

He replied, “You can charge me with what the (expletive) you like. They can’t do more than hang me, can they? If I don’t get hung, old Bird…” (the superintendent was unable to hear the remainder of what prisoner said).

Upon arrival at the Police Office at Eckington, he said, “It was done in a quarrel. I fired through the door. I fired the gun off not with the intention of doing any harm.”

When asked by the magistrates if Taylor wished to ask the superintendent anything, prisoner replied, “No, sir.”

A remand was granted.

Much credit is due to the superintendent and his officers for the manner in which they effected the arrest.

Tuesday, December 5, 1899 – Coroner’s Court

A more miserable day could not be well imagined.

A thick mist, accompanied by heavy downpours of rain, was the prevailing feature, and if anything is required to make a coroner’s inquiry more gloomy than ordinary Tuesday certainly provided all the necessary conditions.

Mr. C.G. Busby, the Coroner for the Hundred of Scarsdale conducted the inquiry, and held his court at the British Oak, Mosborough Moor, a spot about as far removed from civilising influences as any that can be found in or near an industrial centre.

Many of these waited outside the inn in the rain from the time of the inquest commencing, at 10:45a.m., until it ended at 3:30p.m.

The prisoner was taken in a closed-in wagonette from the Eckington police cells to the British Oak.

The largest room in this wayside inn was requisitioned for the jury, the police, and the press.

At the further end of the house the bar was kept lively by a throng of individuals who called “for something hot,”

The affair has caused much excitement amongst the residents of the small village of Mosborough, and the “British public” were represented by a crowd of women, with here and there a more than usually dutiful husband,

A large number of them assembled round the doors of the inn, and stood in the road or on the footpath opposite, in the many cases nearly up to the ankles in mud. many of whom were colliers who had no doubt worked in the same pit as both the prisoner and Henry Bird the husband of the victim.

The rain and mist made no difference to these curious women folk.

Few of them were serious; the majority apparently looked upon the matter as a huge joke.

But what was transpiring in the coroner’s court, which, by the way, was fitted up in the tap room, was of a most serious character, and it was evident that the jury of intelligent men felt all the seriousness and responsibility of the position in which they were placed.

Sitting in one corner of the room was the man Taylor, a diminutive wiry chap, with his cotton shirt unbuttoned at the neck, a red handkerchief being tied round it, and he was handcuffed to a policeman.

Taylor had a much different bearing to that he had exhibited the previous day before the magistrates.

During most of the day he sat with his head resting upon his left hand, which told its own tale of the seafaring life that he once led, a design in Indian ink being as prominent as if it was only put on yesterday.

That Taylor felt his position very keenly no one could question.

Henry Bird collier of Owlthorpe Hill, Mosborough Moor, the husband of the deceased woman Emily Bird, was the first witness called before the coroner.

The poor fellow was terribly distressed and agitated, and it was with great difficulty that the facts of the tragedy were elicited.

He said he was a collier, and lived at Owlthorpe Hill, Mosborough Moor, and the deceased woman, Emily Bird, was his wife, and 46 years of age.

The coroner asked Bird several questions but Bird could not answer for several minutes and sobbed piteously

The coroner asked Bird“When you saw Taylor at quarter to eight that evening was he sober”?

At last Bird said “No; he was in drink.”

The coroner asked “Have you ever had a quarrel with Taylor”?

Bird replied “Never had an angry word with him in my life, Taylor’s wife said she did not know whatever he had done it for”.

Superintendant Talbot asked Bird “Do you remember hearing any threatening language after the gun went off”?

Bird replied “That he did not hear Taylor make any threats immediately after the shot was fired, but later he walked up and down his garden saying he would blow the first (expletive’s) head off who went near him”.

Superintendant Talbot asked Bird “Do you remember the prisoner saying anything else”?

Bird replied “No. Not at that time. Taylor did come running his wife down the lane with the gun and they had to lock her up for safety”.

A Juror asked Bird “Do you think it was Taylor’s intention to kill you instead of your wife”?

Bird replied “Yes, but I never had nothing against him, and did not know anything was against us”.

A Juror asked Bird “Do you think he was aware your wife was at the back of the door”?

Bird replied “He knew we were in the house”.

A Juror asked Bird “Do you think he knew she was at the back of the door?

Bird replied “Yes, she had just slot the bolt and he heard it”.

The Coroner stated that “If a man has a gun in his hand and he intends to kill A, but kills B, in the eyes of the law it is as much wilful murder as if he killed A”.

The Coroner asked Taylor “Do you want to ask any questions”?

Taylor replied “No; I don’t know nothing about it; I was stupid drunk”.

The Coroner advised Taylor “You had better not say anything else”.

The next witness, George Staniforth, said he was a labourer living at Owlthorpe, and was a son-in-law of Henry Bird, and that he lived about 200 yards from his farther-in-law.

Staniforth stated that “He first saw Taylor at about 20 minutes to eight, and at that time deceased and her husband were in witness’ house.

Taylor was then shouting, and Bird went to the door

Taylor was then in the lane, and he heard him threaten to shoot Bird.

A short time after Mrs. Bird had looked for Taylor’s jacket she was going to take the lantern back into her own house, but she had not been away a minute before she came running back.

She appeared to be very frightened, and she locked the door on the inside, and stood with her back against it.

Her husband was then standing about half a yard from her.

Just at this time witness heard footsteps outside the door, and, from the outside, Taylor repeated his former threats.

At the same moment the report of the gun was heard, and the bullet passed through the door, and deceased died immediately.

The police brought Taylor into witness’ house shortly before ten o’clock, and he called Superintendant Talbot an Irish (expletive).

He also said, “Well, if I’ve to be hung, I’ve only to be hung once,” and added that if he was not hung he would shoot old Bird as soon as he came out.

Prisoner was not sober when witness saw him about eight o’clock.

Witness had never heard any quarrel between the parties, but, on the contrary, they always seemed to be on friendly terms”.

Superintendant Talbot asked Staniforth “You were in the inside of your own house and heard a gun fired. After you heard the report did you hear any remarks or threats used”?

Staniforth replied “Not after the report of the gun”.

Superintendant Talbot asked Staniforth “Did you hear any bad language used by any person outside”?

Staniforth replied “I can’t say that I did”.

Superintendant Talbot asked Staniforth “You heard the prisoner use threats just before you heard the gun go off”?

Staniforth replied “Yes, sir”.

Superintendant Talbot asked Staniforth “You were present when I charged the prisoner”?

Staniforth replied “Yes”.

Superintendant Talbot asked Staniforth “You saw me write the charge and the prisoner’s statement in my pocket-book”?

Staniforth replied “Yes, in our house”.

A Juryman asked Staniforth “Was Taylor in a violent temper during the time, or was he very drunk”

Staniforth replied “He seemed in a very violent temper”.

Another Juryman asked Staniforth “Has he ever threatened Mr. Bird before”?

Staniforth replied “Not to my knowledge”.

Another Juryman asked Staniforth “Did he throw a challenge out to fight Mr. Bird when he took his coat off”?

Staniforth replied “I never heard him”.

Another Juryman asked Staniforth “Still you heard him say that he would shoot Mr. Bird”?

Staniforth replied “Yes, sir”.

Another Juryman asked Staniforth “You say he was worse for drink; was he really drunk”?

Staniforth replied “I should say he was about half and half”.

The Coroner advised “Drunkenness is no excuses for a man to commit a crime”.

Eventually the prisoner was arrested by Superintendant Talbot and his men.

In answer to Superintendant Talbot, witness said that after hearing the gun fired he heard a voice, which he recognised as belonging to Taylor, saying: “Thou, canst come out, I have got another barrel waiting for thee,”

The enquiry was then adjourned for lunch.

Taylor’s appearance was altogether a sorry one and pitiable in the extreme.

This was more noticeable after the adjournment, during which time a very painful scene was witnessed that was the interview, kindly allowed by Superintendent Talbot, between Taylor, his wife, and seven little children.

The eldest child was a mere strip of a lad, who has just commenced to earn a few shillings in the pit, and the others ran down to one a few months old in the arms of the mother, who was said to be, and who by her own respectability and the tidiness of her children appeared to be, a most careful, diligent, and hard-working woman.

Words cannot picture the evident agony that Taylor endured.

Directly he saw his children he burst into tears, and heartrending were the sobs of the prisoner who seemed to have abandoned all hope since listening to the evidence of Bird.

How brave a woman can be was now seen!

Caressing her handcuffed husband, she boldly repeated several times “Cheer up, my lad, things are not so bad as they look.”

The little children wept with their father, but the mother shed not a tear until Taylor, handcuffed to the constable, was once again removed to the coroner’s court.

Then when the wife was alone she broke down and despairingly sobbed until other kindly disposed women came forward and consoling her took her away from the court.

Dr. West Jones, physician and surgeon, of Eckington, gave the following deposition:

“On Saturday I was called to Owlthorpe, and went to the house of George Staniforth, and found the body of Emily Bird lying on the floor in a pool of blood.

She was quite dead.

There was a wound in the back of the neck on the right hand side to the right of the middle line. It was a jagged wound, such as would be caused by gun shot”.

He stated that he had made a post-mortem on Sunday.

He further stated that “Above the right shoulder blade there were slight wounds caused by shot.

There was a large jagged wound, which ran inwards and upwards towards the spine.

A large number of fragments of bone could be felt.

The base of the scull was intact, but the two upper bones of the spine were shattered all to pieces, and the spinal cord cut through close to its junction with the brain.

All the other organs were quite healthy”.

Dr. Jones added gravely “My conclusion is, that the injuries described would most certainly mean instant death. I should mention that there were splinters of the wood in deceased’s hair.”

The Coroner asked Dr. Jones “Did you find the shot”?

Dr. Jones replied “I found some in the external wounds, but I could not have followed the other without mauling the body considerably”.

A Juryman asked “Does the doctor think the man was drunk at the time”?

The Coroner advised “I don’t think you can hardly ask that question”.

Dr. Jones stated “I saw Taylor three times on Saturday night”.

The Coroner asked Dr. Jones “Then was he drunk when you saw him”?

Dr. Jones replied “No; I should say he was perfectly sober”.

P.C. Adlington when questioned by the coroner stated “I saw Superintendent Talbot draw the charges from a double-barrelled gun in the lock-up. Each barrel was charged with powder and shot. Taylor was present when this took place”.

The Coroner asked P.C. Adlington “What state was the prisoner in”?

P.C. Adlington answered “He seemed to have had drink, but he was not in that state but what he knew entirely what he was doing so far as I could see”.

The Coroner asked P.C. Adlington “Of course, he was very excited”?

P.C. Adlington answered “Yes, sir, very excited”.

A Juryman asked P.C. Adlington “Were both barrels loaded when you arrested him”?

P.C. Adlington answered “Yes, and he had the gun at full cock”.

The Coroner addressed Taylor “Do you want to ask anything”?

Taylor replied “Yes, sir, I should like to ask that constable whether he got that knife out of my hand or off the table? It very likely was lying on the table as it was the knife my missis always carved with”.

The Coroner asked P.C. Adlington “Did you take that knife out of his hand or off the table”?

P.C. Adlington answered “I took it out of his hand, his right hand”.

The Coroner said that the case was a very curious one indeed.

There did not appear to have been any ill-feeling between Bird and the prisoner Taylor before Saturday, and even in the disturbance the bad language appeared to have been all on one side.

Prisoner’s language was certainly very extraordinary indeed.

The prisoner was said to have been in drink, but that was, he might point out to them, no excuse for the crime committed.

They must remember that if they returned a verdict of “wilful murder” it did not necessarily mean that he would be convicted.

The fact that when charged by Superintendent Talbot the prisoner replied, “They can’t do more than hang me, can they?” did not look as if the affair had been an accident.

They must remember that if Taylor went to the door intending to shoot Bird, but shot the deceased instead, it was just as much murder as if he had shot Bird.

Taylor seams to have been feeling his position more acutely, and looked very pale and dejected throughout the inquiry, and at times seemed scarcely able to control his feelings, and almost broke down when the jury were considering their verdict.

After the jury had considered their verdict in private for ten minutes, the foreman, Mr. John Drabble, intimated that they had come to a decision.

The Coroner asked “What did you find”?

Mr. Drabble then stated “We find that the evidence given in this case is so straightforward that there is no doubt about it, but that it is a wilful act and deed, and we are all unanimous in returning a verdict of wilful murder against Taylor and that he should be sent for his trial upon the capital charge”.

The Coroner addressed the jury “I am bound to say that I quite agree with you”.

The prisoner was retained in custody by the Eckington police, and was removed to the police cells at Eckington, to be brought before the magistrates again the following morning.

At the close of the enquiry one of the jurymen proposed and another seconded a resolution that their fees for attendance should be paid over to the prisoner’s wife, and this was agreed to.

The Coroner then pointed out that the woman by all accounts had done all she could to get her husband away before the crime was committed.

He must add that the police had done all they could to secure the prisoner, and he thought that praise was due to Superintendant Talbort and the police for the manner in which they affected the arrest, and especially was Police Constable Adlington to be commended for the manner in which he acted at the outset sending so smartly for his Superintendent..

Tuesday, December 5, 1899 – Funeral

The funeral of Mrs. Bird the victim of the tragedy took place on Tuesday afternoon at Eckington Cemetery, while the inquest was in progress. There was a large attendance of sympathising people from the neighbourhood, and a constable was present on behalf of the Eckington police.

Wednesday, December 6, 1899 – At the Court of Eckington Petty Sessions

This morning the prisoner was again brought before the magistratesAlderman J.F. Swallow, and Major L. Butler-Bowdon, at the Eckington Police Court on and charged with murder.

Taylor appeared to feel his position acutely, and held his head down during the whole hearing.

His wife was in Court, and was terribly agitated and concerned.

Mr. J.T. Jones, of Eckington, had been instructed to defend.

Captain Holland, the chief constable of the county, was accommodated with a seat on the Bench.

Mr. J.H. Morewood, architect and surveyor, had prepared plans of the scene of the murder, which were handed to the Magistrates.

The fact that the prisoner was being brought before the Magistrates that morning was not generally known, and consequently there was only a moderate attendance at the Court.

Those present listened with intense interest to the evidence, and never had the Eckington Police Court been so silent during the hearing of a case.

Save for a sob now and again from Bird the husband of the unfortunate woman and the voices of the witnesses, hardly a sound could be heard.

The witnesses called were the same as those examined at the inquest with the exception of Jowett, who was not called, and they gave their evidence in a very clear and satisfactory manner.

Bird was totally overcome by grief, and when he told the magistrates how he saw the wood fly from the door and into his wife’s neck, who was standing close to him, with a smile on her face, he completely gave way, and sobbed aloud.

The first witness called was Dr. West Jones, of Eckington, who repeated the evidence he gave at the inquest.

The Chairman asked Dr. West Jones “Did you find the shot”?

Dr. West Jones replied “No, sir, it was probably scattered about in the muscles. I could have found it probably with further mutilating the body”.

The Assistant Magistrates’ Clerk asked Dr. West Jones “What, in your opinion, would cause the wound”?

Dr. West Jones replied “It is one such as would be caused by a gun shot”.

In answer to Mr. J.T. Jones, Dr. West Jones said “As he was going to Owlthorpe he met prisoner in the lane, but did not speak to him then. The next time I saw him it was in the house, and I spoke to the prisoner, and was answered by him. The third time I saw him, was in the cell at Eckington”.

Mr. J.T. Jones asked Dr. West Jones “Did you put any tests to see if he was sober or not”?

Dr. West Jones replied “Yes”.

Mr. J.T. Jones asked Dr. West Jones “Was he at all excited”?

Dr. West Jones replied “No”.

On the application of his solicitor, the prisoner was accommodated with a seat in Court.

Henry Bird, collier, Owlthorpe, husband of the deceased, who appeared to be much affected, and broke down several times, then repeated his story of what happened.

Bird said “He and prisoner lived about 20 yards apart”.

The Assistant Magistrates’ Clerk asked Bird “Have you ever had any quarrel with the man at all”?

Bird replied “No, sir, we have never had an ill word”.

The Assistant Magistrates’ Clerk asked Bird ” You were not at all unfriendly with the deceased, were you”?

Bird replied “No, Sir; not that I know of. If he suspected anything, I don’t know”.

The Assistant Magistrates’ Clerk asked Bird “Was the prisoner sober”?

Bird replied “Well he had a bit to sup”.

John Staniforth, the son-in-law, then told what occurred on the eventful night.

P.C. Adlington and Superintendent Talbot also repeated the evidence they gave at the inquest.

This completed the case for the prosecution, and the prisoner was formally charged.

When asked if he had anything to say, Taylor said, “Not guilty; I reserve my defence.”

The Chairman Stated “Christopher Taylor, you will be committed to take your trial on the charge of wilful murder at the next Derbyshire Assizes.”

Prisoner seemed quite aware of the serious nature of the charge and bowed his head when the Chairman addressed him.

Taylor was afterwards removed to the cells by Sergeant Hughes.

Monday, February 27, 1900 – Derbyshire Winter Assizes

Before the Lord Chief Justice (Lord Russell of Killowen).

The Lord Chief Justice arrived at Derby on Saturday morning shortly after ten o’clock, and opened the commission at the County Hall.

Grand Jury

Fifteen gentlemen were sworn to act on the Grand Jury:

Including Sir John Alleyne, Baronet (Forman)

Colonel J.C. Cavendish

William Cox, Esq.

A.F. Hurt, Esq.

W.H.G. Bagshawe, Esq.

F.N. Mundy, Esq.

Wathall-Wathall, Esq.

Fitzherbert Wright, Esq.

G.F. Maynell, Esq.

C.R. Palmer-Morewood, Esq.

G.W. Peach, Esq.

E.S. Milne, Esq.

F.O.F. Bateman, Esq.

T.O. Farmer, Esq.

Spurrier, Esq.

Oakes, Esq.

R.C.C Newton, Esq.

C.E.B. Bowles, Esq.

D’Arcy Clarke, Esq.

G.H. Taylor Whitehead, Esq.

W.G. Copestake, Esq.

Briggs, Esq.

In charging the Grand Jury His Lordship said he was glad – on the occasion of his first official visit to Derby – to congratulate them that in so large a county as Derbyshire there had been such a considerable decrease in crime.

He had seen the Chief Constable and had looked over the reports prepared for him in regard to crime in Derbyshire during the past few years.

The amount of crime was, he was pleased to say, below the average, and he believed that the decrease was largely due to the higher moral tone of the people and to better education.

The continued prosperous state of trade no doubt also tended to minimise crime.

On looking over the calendar he was glad to note the entire absence of offences of a character which were so frequent in many other countries; he referred to misconduct against females, next to larceny offences against the Criminal Law Amendment Act were the most frequent to be met with, but he learned with satisfaction that no such cases were to come before him at the court.

He hoped that by the firm application of the law and the firm punishment of the offenders they would gradually but surely be stamped out.

They were a disgrace to a civilised country.

Alluding to the business of the Court His Lordship remarked that there were 11 charges against 12 persons.

One was a case of murder and he did not think from the evidence that the Grand Jury would have much difficulty in finding that the woman met with her death at the hands of the prisoner, though there might be circumstances which would cause the charge to be reduced to one of a less serious nature.

The lesser charges were dealt with during the morning session followed by an adjournment.

The Lord Chief Justice (Lord Russell of Killowen) resumed the business of these Assizes at noon, when he proceeded with the only criminal case left, namely, Christopher Taylor collier, Mosborough Moor, near Eckington, was indicted for the wilful murder of Emily Bird wife of a neighbour, on the 2nd of December.

Mr. Bonner and Mr. Magee (Instructed by Mr. C.W. Alderson of Eckington) appeared for the prosecution; prisoner, who pleaded not guilty, being defended by Mr. William Appleton (instructed by Mr. J.T. Jones, of Eckington).

In his opening remarks Mr. Bonner sketched the bare facts of the case, which, he said, was a most brutal, though simple enough, but some difficulty might arise later on which would only be determined by his Lordship’s interpretation of the law relating to murder.

The deceased woman was the wife of Henry Bird a collier, of Mosborough Moor near Eckington.

The people lived within forty yards of each other, and prior to the day in question the accused and deceased’s husband had been on good terms.

On the morning of December 2nd the prisoner was seen near Bird’s house with a gun under his arm, but no words passed between the parties.

There was at that time no quarrel.

At about eight o’clock in the evening Bird was at the house of his son-in-law, who lived next door a short distance from their own dwelling.

Taylor was the worst for drink when Bird heard him in the lane making use of threats towards him, and stating that he would set his house on fire and blow his brains out.

Bird opened the door and told the prisoner that he should take him to the lockup for being disorderly, whereupon Taylor climbed over the wall, took off his coat, and trampled upon the things growing in the garden.

Mrs. Taylor, the prisoner’s wife, then came up, and called out to Bird, “Don’t take any notice of him, he’s drunk.”

Bird replied that he didn’t intend to take any notice of Taylor’s threats, but that he objected to Taylor trampling his plants down, and added that he would have to pay for the damage he had done.

Then Bird went back into Staniforth’s house, leaving Taylor standing in the garden, and complaining that he had lost his coat.

Hearing this, Mrs, Bird offered to help him find it, and for that purpose, left the house to fetch a lantern.

This occupied a short time.

When Mrs. Bird returned to Staniforth’s house she made some communication to her husband, and immediately bolted the door and stood with her back towards it.

No sooner had she done so than steps were heard outside and the prisoner’s voice was heard to say addressing Mr. Bird, “I will blow your head off, you old (expletive),”

Immediately there was the report of the gun, and Mr. Bird, who was standing facing the door, saw his wife fall forward and caught her, when he found that she was dead.

The shot had been fired from outside, and the bullet, having made a small hole in the door some distance from the ground had entered the back of the woman’s neck, and passed up into the skull, causing instantaneous death.

Taylor, who had fired the shot, after using some more threats, went away.

Bird ran out to fetch the police, and two policemen went in the direction of the prisoner’s house for the purpose of arresting him.

On the way to the house they passed a hedge, and the prisoner, who was in hiding behind it, called out that he could hear them “snapping twigs,” and said that he would fire on any one who came near him.

Taylor was later arrested with difficulty, while sitting on the edge of his bed at home for after threatening to shoot his pursuers he was caught with the gun both chambers were fully loaded and the trigger cocked.

Counsel then proceeded to expound the law relating to murder, taking as his authority Mr. Justice Stephen’s work, “A digest of the Criminal Law.”

The prisoner had evidently been drinking during the day, and the question for the jury to decide was whether he was guilty of murder or manslaughter.

That the woman met her death at Taylor’s hands was undoubted, but before he could be convicted of murder it would have to be proved that he was guilty of malice aforethought.

Evidence for the prosecution was about to be called, when Mr. Appleton , for the defence, interposed, and said that from the remarks which had been made by Mr. Bonner it was evident that the case was one of manslaughter, and with the consent of his Lordship and the prosecution he was willing to withdraw his plea of not guilty, and would enter a plea of guilty to manslaughter.

He invited an expression of opinion from Bench on the point.

His Lordship inquired what Mr. Bonner had to say to this on behalf of the prosecution.

Mr. Bonner said that he himself felt that this was a case in which he could not press the charge of murder, and under the circumstances, if his Lordship thought it was a case in which it would be dangerous to admit the possibility of a conviction for murder, he should be perfectly willing to accede to any suggestion that might be made.

His Lordship remarked that “I have carefully read the depositions, and while they point to the commission of a very grave crime, I think that the course suggested by Mr. Appleton was a right one and that the prosecution would be justified in accepting a plea of guilty to manslaughter, and not pressing the change of murder”.

Consequently Mr. Bonner intimated that he would withdraw the charge of murder and the prisoner admitted the charge of manslaughter.

This course was adopted and the charge of murder was then withdrawn, and the prisoner pleaded guilty to the minor charge of manslaughter.

Mr. Appleton addressed a few words to the Court in mitigation of punishment, and stated that there was one detail in the evidence he should have called that ought to be made known, and that was that prisoner was very much the worse for drink, and although drunkenness was admittedly no answer to a criminal charge, it was reasonable to take the fact into consideration in considering the prisoner’s motive.

Further, the deceased’s husband challenged Taylor to come into his garden.

His Lordship commented upon the omission of this latter fact from the depositions.

The prisoner had nothing to say, and his Lordship, in passing sentence, said: The counsel for the prosecution has taken what I conceive the proper course in suggesting that the safest verdict against you in this case would be one of manslaughter.

In addressing Taylor the Judge said “No one who has read the depositions as carefully as I have can fail to observe that you stood in serious peril of your life, and that the more merciful and safer view is to treat this as a case of manslaughter, although it comes dangerously near the crime of murder.

This is a most grievous crime.

Without any justification you have sent this poor innocent woman, who never did you any harm, suddenly, and without a note of warning, to her account”.

The most that counsel for the defence could say for the prisoner was to swell that sickening, heart-breaking, dismal chorus of “Drink, drink, drink.”

His Lordship then sentenced Taylor to five years penal servitude.

The End

Click here to read more: http://www.mosboroughhistory.co.uk/2021/07/24/horrible-murder-near-eckington-as-reported-in-the-sheffield-and-rotherham-independent-monday-december-4-1899/

click here to read more news clips

Click here to read more news clips

Click here to read more news clips

Click here to read more news clips

Click here to read more news clips

Click here to read more news clips

Click here to read more news clips