Lying within the North Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire Coalfield, Mosborough and other local towns and villages share a long history of coal and ironstone mining dating back many centuries.

The earliest documentary reference to coal mining in Mosborough dates from the middle of the 17th. century when a Parliamentary Survey describes “all those Colepits, Delfs, Mynes, or Collieryes now in working and sinking upon Eckington Marsh & Mosborough Moore…”, then in the occupation of Richard Taylor or his assigns[1].

Early History of the Colliery

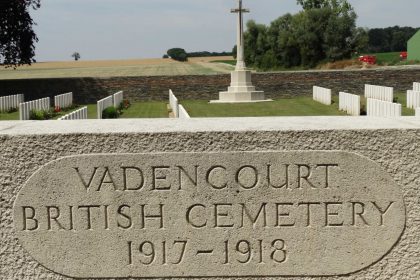

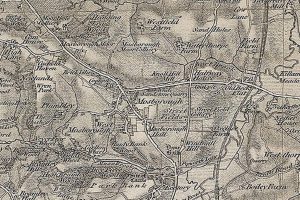

The colliery, known as Swallow’s Colliery, Mosborough Moor, was first depicted on an O.S. map of 1840 as Mosborough Moor Colliery (see below).

Figure 1. Location of Mosborough Moor Colliery in 1840.

The land was formerly part of Lee Field, one of Mosborough’s medieval open fields and then part of the Crown Estate of the Manor of Eckington. It was enclosed in 1796 under the Eckington Enclosure Act 1795. The land was surveyed for the reservation of coal in 1821[2].

It is thought that the colliery was operated from around 1828[3] by Messrs Sales and Tingle, a partnership of coal owners and farmers; that was dissolved in 1831[4]. Philip Sales, one of the partners, lived for a long time at a nearby house (later to become the ‘British Oak’ pub) and afterwards at the Moor-hole on Mosborough Moor.[5].

The colliery was placed on the market shortly after that[6]and it seems likely that it was purchased by Richard Swallow (1801-1877), the eldest son of Richard Swallow (1729-1801) of Attercliffe Forge and Newhall, Sheffield, merchant, and Lord of the Manor of New Hall. Richard Swallow senior died in 1835, leaving substantial legacies to his daughter Mary and his grandchildren. His property at New Hall and the balance of his estate was inherited by Richard junior, his eldest and only surviving son. The New Hall property, including houses and land, was leased after Richard’s move to Mosborough.[7].

In 1839, Richard junior began sinking a second shaft, the Silkstone Main Colliery, nearby. The Mosborough Moor Colliery was closed in 1847. The new shaft was sunk to a depth of 160yds to reach the Blackshale seam of coal (see Table 1).

Table 1. Sections of Strata of the Swallow’s Colliery, Mosborough

Date of Sinking 1839

Lat. 53º’ 19’ 57’ N. Long. 1º’ 21’ 24’ W.

Height above O.D. about 400ft.

| F.T. | IN. | Y.D. | F.T. | IN. | Y.D. | F.T. | IN. | ||

| 1. | Soil | 0 | 0 | 6 | |||||

| 2. | Ratchell | 7 | 2 | 6 | |||||

| 3. | Stone | 50 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 4. | Parkgate coal | ||||||||

| COAL | 2 | 0 | |||||||

| Dirt | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| Coal | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| 59 | 2 | 0 | |||||||

| 5. | Blue Bind | 20 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 6. | Thoncliffe Thin Coal | ||||||||

| COAL | 0 | 1 | 2 | 80 | 0 | 2 | |||

| 7. | Soft spavin | 0 | 2 | 6 | |||||

| 8. | Hard spavin | 3 | 1 | 8 | |||||

| 9. | Band and ironstone | 4 | 0 | 3 | |||||

| 10. | Soft bind | 0 | 2 | 10 | |||||

| 11. | Rock | 0 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 12. | Soft spavin | 1 | 2 | 10 | |||||

| 13. | Bind | 4 | 0 | 3 | |||||

| 14. | Stone | 40 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| 15. | Stone bind and blue balls | 0 | 2 | 6 | |||||

| 16. | Stone | 2 | 1 | 6 | |||||

| 17. | ‘Soap earth’ | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||||

| 18. | Black shale | 5 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 19. | Black shale coal | ||||||||

| 20 | ROOF COAL | 0 | 3 | ||||||

| 21. | Clod | 0 | 9 | ||||||

| 22. | COAL | 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 23. | Dirt | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 24. | COAL | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 148 | 1 | 2 |

About two years later, Richard took the tenancy of Mosborough Hill House, which he bought some years afterwards and considerably enlarged. Richard Ashton was said to have been his steward.[8].

Richard Swallow junior appears to have been married twice, but sadly, there is no record of his first wife, with whom he had two sons:

- Richard (1827-1872), and

- John Fell (1832-1911).

The 1841 Census records him as a coal master, aged 40, living at Mosborough Hill House with his eldest son Richard, aged 15, and two female servants, Sarah and Mary Johnson, aged 25 and 20, respectively. His younger son, John Fell, then aged 10, lived at Housley Hall, Ecclesfield, a boarding school run by Samuel Warburton (1806-1848). When Warburton died seven years later, Richard would marry his widow, Mary Ann.

The early nineteenth century saw a dramatic rise in activity in the mining of the country’s coalfields. The coal mines drew thousands of people off the land and from factories. At its height, Swallow’s colliery was employing up to 100 men and boys from the village of Mosborough. Nationally, stories of how these people lived and worked began to circulate among the general public. They were thought of as wild, hard drinkers who had no morals and were Godless and without education. It was said that women and children worked long hours underground in cramped and dangerous places doing hard, back-breaking work. The public conscience was stirred, and Victorian philanthropists pressed Parliament for some action.

A Royal Commission appointed Commissioners who were dispatched to examine the conditions in the country’s coalfields, take evidence, and report their findings back to Parliament. In 1842, one of the Commissioners, J.M. Fellowes, Esq., interviewed Joseph French, a woodman, at Swallow’s Colliery. His findings were published in the report of the Commission, including a summary of Joseph French’s remarks:

“No. 473. Joseph French, woodman[9]

There is no one besides him in the pit owing to it being holiday week and the canal being drawn off. The shaft is 54 yards deep, the seam 4 feet with headways the same. There are four banks of 13 yards each and two waggon roads 200 yards each but one is not yet worked. The pit is well winded through the engine shaft and the works are dry. There is no wildfire and very little blackdamp. He thinks there is no one in the pit that is under 13 years old and there are six or seven under 18. The shaft is worked with rods to steady the boxes and when drawn up they catch a hook and by means of machinery cover the middle of the pit by an open platform. Three or four are let down and up at a time. They have a flat rope and no chain. The engine is 25 horse power and works the pump. The young men go down at seven to five and have one hour for dinner.”

On 2 May 1848, Richard married Mary Ann (formerly Froggatt, 1806-1858), the widow of Samuel Warburton of Housley Hall, schoolteacher, at St. Peter and St. Paul parish church, Eckington. The officiant at the ceremony was the Reverend Edmund Bucknall Estcourt, Rector of Eckington, from whom Richard would later lease Glebe Land at Mosborough Moor containing a valuable bed of Blackshale Coal.[10], The extent of Richard’s coal leases for Swallow’s Colliery is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Approximate boundaries of coal leases acquired by Richard Swallow at Swallow’s Colliery, Mosborough[11].

In the 1851 Census, Richard describes himself as a Proprietor of Coal Mines; appropriately, it seems, because he also was interested in collieries at Barlborough, Brampton (Inkerman Colliery and Ironstone Pit) and Loundsley Green.[12].

Both his sons were living at Mosborough Hill House with Richard and his wife at this time. Also, there were Christiana and Elizabeth Womersley, female servants from Ecclesfield, aged 22 and 19 respectively, along with Groom, William Holmes of Barlborough, aged 19, and visitors Adelaide, Emma and John Martin, all young people, from Huntingdon.

Around 1853, then aged about 56, Richard Swallow senior withdrew himself from the management of Swallow’s Colliery, handing over its control to his sons, Richard and John Fell. The output from the colliery was between 80 and 120 tons per day, the principal part of which was converted to coke for the Sheffield market in coke ovens at the colliery.

With the growing demand for coal and emphasis on production, the coal industry became a hazardous and precarious occupation. An explosion of firedamp caused the death of Handsworth man, Isaac Platts, aged 32, on 22 January 1851. It occurred in a new working area in the Silkstone Main (formerly Swallow’s) Colliery that was inadequately ventilated. A government Inspector of Collieries attended his inquest at the British Oak,[13]. On 13 March 1854, a young man named George Gregory of Mosborough, aged 19, was killed by a fall of coal there[14]and in September 1856, Henry Oates (1841-1856), aged 15, the son of Francis and Harriet Oates of Mosborough Green, was killed in a gas explosion[15]. Three weeks later, he was buried at St. Peter and St. Paul parish church, Eckington.

Richard senior’s wife, Mary Ann, died at Mosborough Hill House on 26 March 1858 and was buried two days later at St. Peter and St. Paul parish church, Eckington. She was 51 and much respected in the neighbourhood. Little is known of what happened to Richard after that, but he appears to have moved away. He died at Acomb, near York, on 19 January 1877, aged 80[16].

There were also accidents at the Swallows’ Brampton (Inkerman) Colliery. In July 1859, James Briddon of Lower Brampton was fatally crushed by a fall of ironstone,[17]and three men were seriously injured at the ironstone pit when a cage carrying the men became caught up and fell to the bottom of the shaft[18].

The Accident of September 1859

However, the most dreadful accident of all occurred between three and four o’clock in the afternoon on Thursday, 8 September 1859. An explosion and fire at the Silkstone Main Colliery trapped 34 men underground, six of whom were killed. Local newspapers widely reported the accident.[19].

The colliery comprised two shafts about 20 yards apart and 160 yards deep, one used for the pumping of water, otherwise known as the ‘downcast’ shaft, and the other for drawing out the coal; the ‘upcast’ shaft. Miners entered and left the workings through the upcast or drawing shaft. Ventilation was provided by air from the downcast shaft, carried through the workings by a coke-fired engine situated mid-way between the shafts and around 120 yards distant from the bottom of both of them, returning to the surface through the upcast shaft. A broad tramway ran in contrary directions to the northeast and southwest from the bottom of the shafts. Other tramways from the main one then led off to the coal faces. One of these cross tramways commenced about 130 yards from the drawing shaft, following the decline of the coal. An engine was fixed at the head of this cross tramway to draw coal up the incline from the workings below to the main tramway, along which horses conveyed it to the drawing shaft. Attached to the pumping engine were furnace boilers having a barrel-arched brick flue of some two and a half yards wide and 55 yards in length to carry off the smoke to the foot of the upcast. The flue, supported by brick pillars, passed through ungot coal running parallel to the main tramway, with vacant spaces on either side and above it to prevent contact with the coal and possible overheating of the brickwork. It was concluded that the accident arose due to roof coal falling onto the overheated flue.

The first intimation of a problem occurred between half-past two and three o’clock in the afternoon of Thursday, 8 September, when dense smoke was seen to be issuing from the drawing shaft. It was clear that a fire had broken out below ground. The density of smoke in the drawing shaft rendered it incapable of use as a means of escape, so attention was turned to the use of the pumping or ‘downcast’ shaft. However, the wind direction at the surface was carrying smoke over it from the drawing shaft, which was pulled down the pumping shaft at increasing velocity due to the fire’s heat below. Valuable time was lost in creating a barrier of boards and tarpaulins obtained from neighbouring farmers to prevent much of the smoke from entering the pumping shaft.

Below ground, there were around 35 men and boys in the mine, lower than the usual complement of 50, as some had left early. Others had not turned in for work that day. Below ground, the alarm had been raised as soon as the fire was discovered. The men had assembled at the foot of the pumping shaft, awaiting rescue, knowing it was their only means of escape. They had attempted to tackle the fire with water from the pumping engine reserve and buckets, but there was insufficient water and only one bucket. The heat and smoke were overwhelming. Two explosions occurred, one slightly after the fire broke out and a second around a quarter to midnight. None of the men were injured by either of them. A few minutes before four o’clock in the afternoon, beating and thumping were heard from the foot of the pumping shaft, the first indication of survivors. They were unable to signal, as the shaft was rarely, if ever used, except for repair.

Raising and lowering men through the pumping shaft posed many hazards. Smoke continued to enter the mine through the shaft with increasing velocity. Water from springs tapped in sinking continued to fall down it in large quantities. The rescuers required immense courage descending into the mine, unaware of the fire’s progress or the state of ventilation below.

The instrument used for this purpose was a ‘horse’, a triangular piece of wood, raised and lowered by a ‘gin’ and pulley. The men would sit with their feet hanging down, tied or holding on to a rope at its apex. However, there were no means of guiding the ‘horse’ in its ascent, meaning that rescuers had to be deployed at two staging points in the shaft, one 40 yards from the surface and another about 60 yards from the bottom to prevent it being dashed against obstructions.

The horse was successfully lowered by six o’clock in the afternoon, and the first man rescued, Richard Blackburn, was brought to the surface. The miners had waited in darkness for several hours, not knowing the efforts made above ground to affect their rescue. During this period, the fire had continued to progress. The doors across the main tramway were already in flames before the recovery commenced. A state of panic became apparent when the rope was first let down. Ten or more men attempted to cling to it, and valuable time was lost in convincing them to relinquish their grasp.

At around 10 o’clock, the wind direction changed, significantly improving the conditions. Difficulties remained in getting lights safely to the bottom because of the quantities of water falling down the sides of the shaft. Eventually, the problem was overcome by using the lamps of police officers, several of whom by then were present. At around 11 p.m., two fire engines and brigades arrived, one from the Sheffield Office and Liverpool and London. However, it was considered too dangerous to throw any quantity of water down the shaft until the men could be got out, and their services were not required. The Secretary of the Sheffield Office had travelled to the incident by cab in advance of the fire engine and offered his cab to convey the injured and survivors.

It was not until four o’clock on Friday morning that the last man that could be found alive, George Gee, was brought to the surface. Later that morning, at around 9 or 10 o’clock, the bodies of Naboth Kirkby and Hugh Bird were recovered and placed in the club room of George Booth’s ‘British Oak’. After all those alive had been brought out, the fire engines played water into the upcast shaft until around 8 p.m., at which point they left.

A further attempt to recover the bodies was made on Sunday morning, but it proved unsuccessful owing to the heat and smoke at the foot of the downcast shaft. A fan was erected at the top of the shaft on the following day, which drove a current of air into the mine. It was hoped that a further attempt to recover the bodies could be made in another day or so[20],

The Fatalities

Those who died were:

- Hugh Bird (1843-1859), aged 17 years, trammer, who was baptised at St. Peter and St. Paul parish church, Eckington on 28 May 1843, the son of Christopher Bird (1812-1885) of East Street, Mosborough, sickle maker, and his wife Mary Ann (1814-1870). He was killed by Naboth Kirkby falling down the colliery shaft on top of him. Mr Hedley, the government inspector, had seen them lying together, and Kirkby was on top. Hugh Bird was buried at St. Peter and St. Paul parish church, Eckington, on 11 September 1859, on the same day as Naboth Kirkby, possibly with a joint funeral.

- Charles Dowman, a boy, about whom nothing is known.

- Naboth Kirkby (1840-1859), aged 19 years, filler, who was baptised at St. Peter and St. Paul parish church, Eckington on 12 April 1840, the son of John Kirkby (1808-1876) of West Street, Mosborough, shoemaker and village constable, and his wife Mary (formerly Glossop, 1805-1859). He was being raised from the bottom of the colliery shaft with Frith Beresford and a third man by Mr Hedley, the government inspector. There were two ‘horses’, and Kirkby was on the bottom. Hedley asked the boy if he was safe, and he replied “Yes”, at which point the hook by which he was attached became loose, and he fell to the bottom of the shaft and was probably killed instantly. He was buried at St. Peter and St. Paul parish church on 11 September 1859 on the same day as Hugh Bird, possibly with a joint funeral.

- Charles Meggitt (c.1846-1859), aged 13 years, hurrier. His body was not recovered until Sunday, 8 April 1860. It had become skeletonised and could only be identified by his shirt and clogs by that time.[21]. He had called out to his father to get him, but Meggitt grasped the arm of another boy (John Kay), thinking it was his son. When he returned, his son could not be found. He was supposed to have fallen from one of the landing stages at the same time that Naboth Kirkby fell and died of suffocation from smoke[22]. Son of Richard and Sarah Meggitt of Owlthorpe, Mosborough.

- Henry Stevenson (c.1849-1859), aged ten years, door tenter or trapper, who was baptised at St. Peter and St. Paul parish church, Eckington on 28 January 1849, son of John Stevenson (1810-1887) of West Street, Mosborough, farm labourer, and his wife, Lydia (formerly Whitehead, 1818-1869). His body was not recovered until some months later, and having become skeletonised, could only be identified by his clothing[23]. He was buried at St. Peter and St. Paul parish church, Eckington, on 16 May 1860.

- Henry Stimson, a boy, about whom nothing is known.

The Men Rescued from the Mine

Those rescued were:

- Benjamin Barber, filler.

- John Barker (b. 1846 at Gedney, Lincolnshire), aged 13, a hanger-on at the bottom of the incline, son of Emmanuel and Jane Barker of Eckington Marsh.

- Henry Bailey (b. 1844 at Mosborough), hurrier, aged 15, son of James and Mary Bailey of West Mosborough.

- Adam Bird (b. 1840 at Mosborough), aged 19, son of Christopher and Mary Ann Bird of West Street, Mosborough. Brother of Hugh Bird, who was killed in the accident.

- Richard Blackburn (1838-1919), coal getter, aged 21, son of John and Elizabeth Blackburn of Ridgway. The first man to be brought out of the mine.

- William Bramall (1831-1905), aged 28, coal getter, of Hackenthorpe, husband of Eliza. Brother of George Bramall, deputy of the colliery at the accident.

- John Broadhead, coal getter,

- Thomas Dean (b. c.1844), hurrier, age 15, son of Mary Dean, widow, of Mosborough Green.

- George Gee, hurrier, the last man to be found alive and rescued at around 4 a.m. on Friday.

- Joseph Glasby (b. c.1841 at Renishaw), filler, age 18, son of Thomas and Elizabeth Glasby of Mosborough Moor.

- Herbert Hawkins (1836-1908), age 23, was born at Heage, Derbyshire, aged 23, engine tenter, of Eckington Marsh, husband of Selina.

- William Coggan (alias Holden), hanger-on.

- William Shephard (b. 1843 at Killamarsh), aged 17, horse driver, son of James and Elizabeth Shephard of Holbrook Road, Halfway,

- James Mitchell, (b.c.1840 at Mosborough Moor), age 19, a hanger-on at the top of the incline. Son of William and Mary Mitchell of Mosborough Moor.

- Richard Herring (1837-1918), coal getter, aged 22, son of John and Ann Herring of Hackenthorpe.

- John Kay (b. c.1838 at Mosborough), coal getter, age 21, son of George and Sarah Kay of Mosborough Green.

- Joseph Kay (b. c.1842 at Mosborough), age 17, son of George and Sarah Kay of Mosborough Green.

- William Kay (b. c.1840 at Mosborough), filler, age 19.

- John Lomas (b. c.1834-1897, in Eckington), coal getter, age 25. Son of William and Martha Lomas of Pound Hill, Mosborough.

- Richard Meggitt (b. c.1816 at Lampton, Lincolnshire), filler, age 43, of Owlthorpe, husband of Sarah Meggitt.

- William Meggitt (b. c.1848 at Spridlington, Lincolnshire), tenter, age 11, son of Richard and Sarah Meggitt of Owlthorpe.

- John Metcalfe (b. c.1841 at Eckington), hurrier, age 20, Son of John and Mary Metcalfe of Eckington.

- John Oates (b. 1834 at Mosborough), coal getter, age 25. Son of Francis and Harriet Oates of Mosborough Green.

- George Plant (1830-1910) coal getter and former deputy steward, age 29, of Turnpike Road, Mosborough, Former landlord of the George and Dragon. Husband of Jane Plant.

- Isaac Plant (1828-1902, coal getter, age 31, of West Street, Mosborough. Brother of George Plant. Husband of Mary Plant.

- Septimus Plant (1842-1896) coal getter, age 17. Son of Isaac and Mary Plant of West Street, Mosborough.

- Alfred Riley, filler.

- William Shepherd (b. 1843 at Killamarsh), horse driver, age 15. Son of James and Elizabeth Shepherd of Owlthorpe, Mosborough.

- Thomas Sisson (b. 1843 at Mosborough), age 16, hurrier, Son of John Sisson, colliery underground steward, and his wife Sarah, of Turnpike Road, Mosborough.

- William Stevenson, (b. 1844 at Eckington), age 15, hurrier. Son of John and Lydia Stevenson of West Street, Mosborough.

- John Turner (1838-1910), age 21, filler, Son of Thomas and Sarah Turner of West Street, Mosborough.

- Henry Wood, filler[24].

The Rescuers

Among those taking the lead in the rescue operations were:

- Frith Beresford (1828-1897), age 32, of Bridle Road, Mosbrough, husband of Martha and father of eight children. He was an engine tenter in a neighbouring pit of Mr Wells, was said to have been one of the most courageous of those who rendered assistance. He was near the Crown Inn at Mosborough when he was first informed of the accident by John Sisson, the colliery underground steward. Descending into the mine after the first seven or eight had been brought up, he went to the bottom and brought up two men, one on each of his thighs and Naboth Kirkby clinging to the rope above, to the lower stage. It was from here that Kirkby fell to his death. He took the remaining two miners, including John Turner, to the surface. At midnight, he was relieved and returned to the rescue effort at about three o’clock, descending once more to the lower stage, where he spoke to John Kay, but his rope signal was misunderstood, and he was raised again. He went down once more to search for Charles Meggitt but could not find him. A subscription list was opened at the British Oak pub to reward him, Ellis Ulley and others for their efforts. It raised a sum of £15 17s 3d, which was presented to them at George Booth’s ‘British Oak’ by a committee consisting of the Reverend E. B. Estcourt, Vicar of Eckington, the Reverend J. Eastwood, Mr J. Wells, Esq., and Mr Harwood, Esq.[25].

- John Sisson, age 44, colliery underground steward of Turnpike Road, Mosborough, was instrumental in erecting the screen around the pumping shaft to reduce the amount of smoke being drawn into it. He then followed George Foster down to the first stage around 50 yards from the surface to steady the men as they came up and prevent them from being injured by the stays. He later went to the bottom of the shaft around eight o’clock and brought two men to the surface.

- George Foster (1817-1884), age 43, blacksmith and Primitive Methodist Preacher, was the first to descend the pumping shaft on the ‘horse’ at around five o’clock. He alighted at the bottom stage, around 60 yards from the bottom, communicating with the surface through a signal rope and guiding the ‘horse’ down to the men below.

- Mr Hedley, the government inspector of mines, followed Thomas Sissons down to the first stage. After two men who had been landed there were taken to the top, he took the ‘horse’ to the bottom of the shaft and returned with three men, one of whom was Naboth Kirkby. He landed them at the top stage, and from there, it was agreed that he would take them up one by one. Kirkby was the first to go, but no sooner had the rope been made tight, the chain gave way, and he fell to the bottom, and the ‘horse’ along with him. After taking another man to the top, he brought out John Turner.

- Ellis Ulley (b. 1842 at High Lane), age 17, son of Edward and Elizabeth Ulley of High Lane, a workman at Mr Well’s pit. He had just landed two of the survivors at the surface and was suspended at the mouth of the pumping shaft ready to descend again when the second of the two explosions occurred at a quarter to twelve. Fortunately, apart from the effects of breathing sulphur, he was uninjured.

- Joseph Wells of Eckington (1816-1873), Proprietor of Moor Hole Colliery, deserved credit for supervising the rescue operations. He and Mr Seymour, manager of Mr Barrow’s Staveley Works, were said to have rendered valuable assistance, along with Mr Harwood of Eckington, and Mr John Thomas Jones (1828-1894) of Eckington and Mr Thorpe of Staveley, surgeons. Richard and John Fell Swallow were also said to have been ‘very energetic’.

- Reverend Edmund Bucknall Estcourt, Rector of Eckington, provided sustenance and blankets for the rescued and ensured they were delivered to their homes.

After the Accident

The fire below ground continued to rage for some time after the accident, and attention was turned to how the bodies of Charles Meggitt and Henry Stevenson were to be recovered. Owing to the accumulation of bad air and the inefficient state of the ventilation in the workings, no one had been able to reach the bottom of the shaft. Wooden piping was introduced down the pumping shaft for ventilation, and a large volume of water was pumped into the pit at the rate of 200 to 300 gallons a minute.[26]. It was concluded that the only effective way to extinguish the fire would be to allow the workings to fill will water, which could be expected to take several months. The two remaining casualties were not recovered until 8 April 1860.

Unfortunately, a further death occurred during the recovery operation. Samuel Hobson (c.1794-1860), aged 66, was seriously injured when a quantity of rock and earth fell on him. He was conveyed to Sheffield Infirmary, where he died on 7 March 1860[27].

Inquest into the deaths of Naboth Kirkby and Hugh Bird

On Saturday, 10 September 1859, an inquest on the bodies of Naboth Kirkby and Hugh Bird was opened by H.E. Walker, Esq., M.D., deputy coroner, but he took no evidence. The hearing was held simply to enable the bodies to be interred, and it was adjourned to 5 October. The boys were buried at the parish church of St. Peter and St. Paul, Eckington, on 11 September 1859, possibly at a joint funeral conducted by the Rev. E.B. Estcourt, Rector of Eckington.

The adjourned inquest was opened on Wednesday, 5 October[28], at the ‘British Oak’, before the Coroner, Mr C.S.B. Busby, Esq., of Chesterfield, and the following jury:

- Joseph Wells, Esq., Eckington, foreman;

- Charles Rotherham, Esq. of Mosborough Hall;

- Mr Frederick. Keeton, Mosborough;

- Mr John Ibbotson Hayes, Mosborough;

- Mr Septimus Staton, Mosborough;

- Mr Luke Worrall, Mosborough;

- Mr George Booth, Mosborough;

- Mr George Cadman, Mosborough;

- Mr Joseph Alton, Plumley;

- Mr George Widdowson, Eckington;

- Mr Murther McEvoy, Eckington, a former deputy steward at the colliery;

- Mr Thomas Carline, Eckington.

Frith Beresford gave evidence at the hearing, along with Mr Hedley of Derby, the government inspector of mines. Beresford said that he had been standing by the Crown Inn in Mosborough between three or four o’clock in the afternoon when he was first told of the incident by John Sisson. He went to the pit and saw a significant quantity of smoke coming out of the drawing shaft. People were erecting barricades around the downcast.

Mr Hedley stated that there was a rope connected to the working shaft from a horse gin, but there was no chance of anyone going down it owing to the quantity of smoke. He had seen John Sisson attending to the erection of a barricade over the pumping shaft and had seen George Foster descend the shaft on the ‘horse’ at around 5 o’clock. He recalled that Richard Blackburn was the first man to be brought to the surface. Mr Hedley followed George Foster and John Sisson down to the first stage after seven or eight men had been brought out. He remained there to steady the men as they came up and later descended to the foot of the shaft and brought up Naboth Kirkby (see description of what then transpired above).

After the accident with Naboth Kirkby, he brought up two further men, including James (John) Turner. He didn’t see the body of Naboth Kirkby until it was brought to the surface the following morning. Mr Seymour of Staveley recounted how he had descended into the shaft at around three o’clock but only got to within eight yards of the bottom, and there remained suspended as there was no signal rope. He instead shook the rope by which he was suspended and was raised again to the surface. He had spoken to John Kay and promised to return for him. He recalled seeing George Gee go down to bring out his son.

Mr Wells asked the witness how he thought Hugh Bird came to his death, to which the witness replied that he believed that Naboth Kirkby fell upon him and killed him on the spot.

George Plant, a miner at Silkstone Main Colliery, was the next to give evidence. He was working at the south level at the time of the accident, and two boys came to tell him about the fire at around four o’clock. He described what he saw when he got to the drawing shaft and the efforts to extinguish the fire. On reaching the foot of the pumping shaft with the other men, he said he saw the bodies of Naboth Kirkby and Hugh Bird.

The discussion then turned to the arrangements for the cleaning of the flue. A quite combative exchange took place between Mr McEvoy, Mr Widdowson and the Coroner as to the cause of the accident. McEvoy argued that the deaths occurred due to failure to clean the flues. At the same time, the Coroner asserted that the jury’s function was to determine the immediate cause of death of the two boys. After this exchange, Frith Beresford and George Plant were re-examined. A further argument between the Coroner and certain jury members ensued, particularly concerning the culpability of John Sisson, the steward.

Eventually, the jury concluded that Naboth Kirkby had come to his death by the chain of the ‘horse’ becoming accidentally detached, but regarding Hugh Bird, they recorded an open verdict, being “found dead” but with insufficient evidence to show how he came to his death.

Inquest into the death of Charles Meggitt

An inquest was held on Thursday 12 April 1860[29] into the death of Charles Meggitt, age 13, hurrier, before the Coroner, C.S.B. Busby, Esq., at the ‘British Oak’ pub, and the following jury:

- Joseph Wells, Esq. of Eckington, foreman;

- Charles Rotherham, Esq. of Mosborough Hall;

- Mr George Booth, Mosborough Moor;

- Mr Murther McEvoy, Eckington;

- Mr George Widdowson, Eckington;

- Mr William Turner, Mosborough;

- Mr Luke Worrall, Mosborough;

- Mr Septimus Staton, Mosborough;

- Mr Joseph Alton, Plumley;

- Mr Henry Lant, Eckington;

- Mr Thomas Carline, Eckington;

- Mr James Rose, Mosborough;

- Mr William Keeton, Mosborough.

Also present was Mr Hedley of Derby, the government inspector of collieries. After the discovery of the fire. Richard Meggitt, the boy’s father, had the deceased and his other son, William, with him. Using a ladder, he and others had reached the lower stage of the pumping shaft, but the second explosion in the mine caused his son Charles to fall to the bottom of the shaft. About a quarter of an hour after the second explosion, he got onto the ’horse’ and shouted to be lowered to his son, but instead, the ‘horse’ was raised, and he, along with the boy John Kay who he carried up with him, were rescued. He had heard his son calling for his father to help him, but he could not do so.

When Charles Gee went down the shaft to bring his son out, Charles Meggitt was still alive. He thought he was at the bottom of the shaft but could not see him; the shaft was so full of smoke. He could see the fire burning “like a furnace” and could hear the noise from falling and burning coal. He spoke to Meggitt, but his moans were getting gradually weaker. He believed the boy to be dying. Faith Beresford was the last man to go down the pumping or ‘downcast’ shaft on the accident night. He went explicitly to fetch Charles Meggitt but could not go as far as the bottom of the shaft because he considered it too dangerous. He shouted for the boy but could not hear him.

John Sisson, the colliery steward, told the inquest that he had found and recovered the body of Charles Meggitt on Sunday morning, the 8 April 1860.

In his summing up, the Coroner concluded that the bulk of the evidence showed that the fire did not arise from the non-sweeping of the flue. He then turned to the possibility of criminality in getting the men out of the pit. In this respect, he drew attention to an error on the part of John Sissons, the colliery steward, in not stopping up the current of air leading to the fire. However, he did not consider that there was sufficient evidence to charge anyone with criminal neglect.

The jury returned a verdict that Charles Meggitt was accidentally suffocated and killed by smoke from a fire in the mine, caused by coal falling from the roof of the pit onto the flue, but that the fire would not have occurred if proper precautions had been taken by John Sissons, the underground steward. The jury foreman also told Mr Swallow that he should employ men who would see that the colliery rules were carried out and that the colliery was adequately managed.

There was much discussion and evidence at the inquest regarding the routine practice of cleaning the flue of soot. One of the jurymen, Mr Murther McEvoy, draper of Eckington, argued that a failure in this process had led to the fire, but this suggestion was countered by Mr Hedley, the government inspector, who thought it more likely to have been caused by a fall of coal onto the flue.

Inquest into the death of Henry Stevenson

An inquest into the death of Henry Stevenson was held on Tuesday 15 May 1860, before the Coroner, Mr C.S.B. Busby, Esq. Similar evidence was given to that heard in the earlier inquests by William Holden, George Plant and George Brammall, Herbert Hawkins and John Sissons and a verdict of ‘Accidental Death’ was returned.[30].

Return to Normality

At the 1861 Census, John Fell Swallow and his brother Richard, both unmarried, lived at Mosborough Hill House, along with the housekeeper, Ann Harmaford, married, aged 40, and general servant Mary Hollinsworth, aged 21.

The Silkstone Main Colliery was worked out in 1863 and closed in 1864[31]. The 1871 Census records Richard and John Fell Swallow living at Mosborough Hill, with Henry Staniforth residing at Mosborough Hill House, suggesting either some confusion of names or that the brothers had relocated to a different property. They are both described as “Out of trade”, indicating that they had given up the coal mining enterprises. Also living with them were Ann Goodwin of Bradfield, cook, aged 21, and Elizabeth Eggleston from Nottinghamshire, a housemaid, aged 27.

The Census was taken shortly before the death of Charles Rotherham of Mosborough Hall (1805-1871). Presumably, the two families were well acquainted socially and were known to each other since Charles Rotherham acquired the Hall in 1843. Rotherham had served as a juror at the inquests following the Silkstone Main Colliery disaster. John Fell Swallow was appointed a trustee of Rotherham’s Mosborough Hall estate. He had responsibility, amongst other things, for collecting payments for the Mosborough Hall collieries until the property was inherited by Henry Walker (1830-1891), the husband of Charles Rotherham’s eldest daughter, Therese Eleanora Susannah (1830-1898). He was still working coal under the Mosborough Hall estate, as a joint trustee with George Marriott (1806-1874, Charles Rotherham’s brother-in-law) in 1873[32].

In this connection, John Fell Swallow would have been a regular visitor to the Hall. It was here that he met Mary Ellen Knight (1845-1926), Governess to Henry and Therese Walker’s children, to whom he would be married in October 1872 at Festiniog, Wales. Shortly before this happy event, his brother Richard had died at Mosborough Hill on 25 August 1872, aged 42. He was buried at the Old Chapel, Attercliffe[33].

John and Mary Ellen had a daughter, Maria (1874-1965), in 1874. The 1881 Census records the family living at Mosborough Hill, with Marian C. Hague, a teacher and governess, aged 20, from Sheffield, Agnes A. Daniels, aged 25, a cook, from Sheffield and Harriet A. Youle, a housemaid, aged 18, from Handsworth.

Becoming an active participant in local affairs, John was elected a trustee of the Joseph Stones Endowed School[34], and in 1885 he offered land in Mosborough to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners as a gift for a new church to be called All Saints, Mosborough, but the conveyance was not proceeded with[35]. He had become a Justice of the Peace for the county in 1887 when he marked Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee with celebration for his seventy tenants at Moor Hole[36]. John also supported the opening of “a grand public reading room” at Mosborough Common[37].

In 1891, John and Mary Ellen were still residing at Mosborough Hill, with a cook, Alice Barker of Ridgeway, aged 17 and housemaid, Ellen Fiddler of Ridgeway, aged 16. Their daughter, Maria, had been sent to Cheltenham Ladies’ College[38]. In 1898, John was called to give evidence at the High Court of Justice in connection with the case of Sitwell v. Worrall, a claim by Sir George Reresby Sitwell (1860-1943), Lord of the Manor of Eckington, against John Worrall (1846-1919) of Mosborough Hall Farm, who was working coal under the Mosborough Hall estate. Sitwell contended that the coal was being worked without the consent of the Lord of the Manor, contrary to ancient custom. By this time, John Fell Swallow had become an Alderman of the Derbyshire County Council, representing Eckington Parish Council.

By 1901, the family was recorded as living at Moorhall in Mosborough, and Maria, aged 27, had returned from College. Also living at the house were Ellen Bradford, 31, a housemaid from Lincolnshire; Mary White, 30, a cook from Deepcar; and Annie Cooper, 17, a kitchen maid from Handley. Also resident at the house was Elizabeth Roberts, 26, a ‘sick nurse’ from Glamorgan, suggesting that someone in the family was unwell.

In 1911, the Census recorded that John and Mary Ellen lived at Mosborough Hill, a house of nine rooms, with servants; Jane Briddon, 45, from Wellington, Shropshire, Elizabeth Elsie Deacon, 21, from Swindon, and Lily White, 16, of Derbyshire. Their daughter Maria had married Frank Charlton Jonas (1882-1917) of Vicarage House, The Green, Duxford, Cambridgeshire, son of George Jonas (1839-1908), deceased, farmer of 1200 acres, and his wife Jane Ellen (1839-1889), deceased, at St. Martins in the Field, London on 13 October 1908.

John Fell Swallow died on 19 November 1911 at Mosborough Hill.[39], aged 79, and was buried at Eckington Cemetery. His wife, Mary Ellen, died at Mosborough Hill House on 26 February 1926, aged 81, and was buried at Eckington Cemetery.

[1] Survey of the Manor of Eckington, National Archives, LR2/279.

[2] Mosborough: Lands on Mosborough Moor surveyed for the reservation of coal. Description: Watermark 1821. Sheffield City Archives, F.C. ECo 13S

[3] (1) Measures taken from the old maps to set out the boundary of Messrs Sayles and Tingle’s minerals purchased of the Crown and situate on Mosbrough Moor, 1 item, Pages 30-33 [1828]. Sheffield City Archives, Fairbanks Collection, FC/FB/197. (2) Mosborough Moor: map of parts of Mosbrough Moor in the parish of Eckington in the county of Derby under which the coal is sold to Philip Sayles and Thomas Tingle. Sheffield City Archives, Fairbanks Collection, FC/P/ECo/14S.

[4] Partnership Dissolved: Sayles and Tingles, viz. Philip Sayles Thomas Tingle and Joseph Tingle, Mosborough Moor and High Lane, both in Eckington, Derbys. Coal owners and farmers. Dissolved: 6 April, Gazetted: 29 November. Paget, J.W., The Law Advertiser, 1831, p. 501.

[5] Foster, G., Reminiscences of Mosborough in the Present Century, 1886.

[6] Notice of sale of Mosborough Moor colliery of Messrs Sayle and Tingle under 47 acres at Mosbrough Moor Hole with Top Birley, Top Manor and Sheffield coal beds. Sheffield Independent, 21 April 1832.

[7] West Yorkshire, England, Electoral Registers, 1840-1962, West Riding, No. 531, Brightside Bierlow Township, 1842. Tenant: John Sanderson.

[8] Foster, G., Reminiscences of Mosborough in the Present Century, 1886.

[9] Joseph French (1808-1891) lived on Colin Green and was a carpenter like his father, Abraham. He enjoyed a successful career in the mining industry, probably working for the Swallow family, first as a carpenter and later as a colliery clerk and bookkeeper. Joseph would have been around 31 at the time of the Commissioner’s visit. He never married but retired to Ridgeway, where he died in 1891, aged 82, and was buried in Eckington Cemetery.

[10] Lease: The Reverend Edmund Bucknall Estcourt, clerk, Rector of Eckington, to Richard Swallow of Mosbrough Moor in the parish of Eckington. Description: The bed of Blackshale coal under the South Part of Hanging Lee, etc. Sheffield Archives, ADC/6/3/11

[11] Derived from evidence given at the High Court of Justice, Chancery Division, by John Fell Swallow before Mr Justice Byrne in the case of Sitwell v. Worrall, on 18 February 1896, reported in Sitwell v. Worrall, Trials, 1600-1926, Justice Byrne, Evidence and Judgement, 1898, pp. 168-188. John Fell Swallow had bought up most of this land before 1873, Return of Owners of Land, 1873: John Fell Swallow, Mosborough Moor, 38a. 3r 1p. (annual rental value £106 15s). John Lee of Mosborough Brick and Tile Works was the principal tenant, having provided drains in 1888. (Bound volume of plans of fields in Mosbrough Hill estate, marked with drains; inside a bill to J. F. Swallow from John Lee (the tenant of many of the fields), Mosbrough Brick and Tile Works, for drains supplied. Sheffield Archives, ADC/6/3/14).

[12] Probably with his sons working as agents and trading as Messrs Swallow, a partnership of William Richard Swallow (possibly a relative) and John Fell Swallow. The partnership was dissolved on 28 April 1858. Perry’s Bankruptcy Gazette, 15 May 1858.

[13] Derbyshire Courier, 25 January 1851.

[14] Derbyshire Courier, 18th March 1854.

[15] U.K. Coal Mining Accidents and Deaths Index, 1878-1935.

[16] York Herald, 29 January 1877.

[17] Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald, 30 July 1859.

[18] Derbyshire Courier, 17 November 1860.

[19] Derby Mercury, 14 September 1859, Derbyshire Courier, 17 September 1759, Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald, 17 September 1859, Cheltenham Examiner, 14 September 1859. Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 10th September 1859, Sheffield Independent, 10 September 1859, Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald, 8 October 1859. The newspaper reports were remarkably consistent in their accuracy, although the names of those involved did vary slightly. The numbers cannot be relied upon with confidence.

[20] Derbyshire Times and Chesterfield Herald, 17 September 1859.

[21] Sheffield Independent, 14 April 1860.

[22] Coal Mining Accidents and Deaths Index, 1878-1935.

[23] Sheffield Independent, 19 May 1860.

[24] John Sissons, the colliery steward, had requested treatment for Wood, who had been badly injured by burning in the disaster, from a surgeon named Henry Liversidge. The surgeon made a claim against Sissons for £2 10s 6d. for the treatment provided at Chesterfield County Court. Messrs. Swallow had refused payment on the ground that it had never been their custom to pay medical bills for accidents. Derbyshire Courier, 30 January 1858.

[25] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 11 November 1859.

[26] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 6 October 1859.

[27] Coal Mining Accidents and Deaths, 1878-1985; Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 9 March 1860.

[28] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 6 October 1859.

[29] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 13 April 1860.

[30] Sheffield Independent, 19 May 1860.

[31] Sitwell v. Worrall, Trials, 1600-1926, Justice Byrne, Evidence and Judgement, 1898, p. 186.

[32] 2 July 1873. Copy of a letter indicating that John Swallow and Mr Marriott, trustees of the late Charles Rotherham of Mosborough Hall, had been working coal under copyhold property of Mrs Worrall. Sitwell v. Worrall, Trials, 1600-1926, Justice Byrne, Evidence and Judgement, 1898, p. 130.

[33] Funeral/memorial card for Richard Swallow, aged 42, of Mosborough Hall. Interred at the Old Chapel, Attercliffe. Sheffield Archives, A.C./59/39

[34] Derbyshire Courier, 5 January 1884.

[35] Sheffield Archives.

[36] Derbyshire Courier, 25 June 1887.

[37] Foster, G. Reminiscences of Mosborough During the Present Century, 1886

[38] Founded in 1853, the Cheltenham Ladies’ College was established to provide “a sound academic education for girls”. In 1873, the College moved to its present location (2021), the site of the original Cheltenham Spa. Maria was a resident at Farnley Lodge, a boarding house still in existence, connected with the College in 1891.

[39] London Gazette, 19 November 1911.