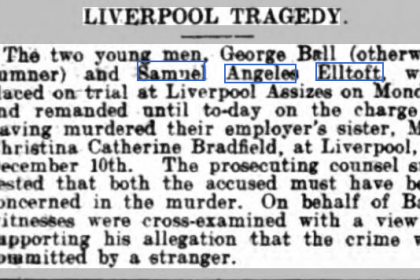

Extract from the “Eckington, Stavely & Woodhouse Express”, October 8th 1904

A MOSBRO’ WORTHY.

Mr John Ibbotson Hayes, School Master & Registrar

A number of years before Charles Dickens, the philosopher of Gadshill evolved from his fertile brain the various volumes of worldwide popularity and interest, in which are vividly portrayed country schoolboy experiences, the nature of the education, the adoption of its teaching, the pains and penalties inflicted, and the duties to be performed: as also the habits, trials and peculiarities of the Master. Before the ever-to-be-remembered and original character, ‘Domine Sampson’ pronounced his exclamation of surprise, “prodigious” there had appeared at Mosbrough, near Eckington, in the capacity of a national schoolmaster, a graceful, polite and good-mannered young man, who had partaken freely of the ‘tree of knowledge’ and there he continued to reside, until a life extending to ninety years save eleven days merged peacefully into eternity.

Mr. Hayes for the period of thirty two years was the village schoolmaster and, for the greater number of years, fifty, register of births and deaths for the parishes of Eckington, Killamarsh and Staveley, within the jurisdiction of the Chesterfield Poor Law Union; the latter office he resigned in 1885, in the 84th year of his age, being born at Worksop on the 20th July 1801. Mr. Hayes was the son of Samuel Hayes of that place, Builder and Contractor (who died relatively young, leaving his son the handsome and very useful sum of £800) and who was educated at a private school at Laughton-en-le-Morthen near Rotherham, where he remained as assistant and advanced student for several years, after the usual terms and age.

Having chosen the career of schoolmaster as his field of labour and usefulness, an opening presented itself for commencing duties on his own account at Ridgeway on completion of a new school there. In 1823, this opportunity was accepted, although there was no endowment, excepting “influential inducement”. For about two years only, Mr. Hayes remained at Ridgeway, a more important mission becoming vacant in consequence of the death – under distressing circumstances – of Mr. Richard Marsh, the master of the endowed school at Mosboro’: this was offered by the trustees to and accepted by him in 1825 and retained as a permanency, as from that date, until the year 1857, the village did not experience the pleasure or inconvenience of a change of schoolmaster.

The endowment was not a liberal one, but very acceptable, derived from lands derived from Mr. Joseph Stone in 1680 for the education of fifteen scholars free from charge. The properties consist of three closes of land on Beighton Hill 4a3r0p, one field on Mosbro’ Green 2a1r20p and one in Street Field 0a2r22p; there was also at the time of appointment a good dwelling house with garden and croft adjoining for the master. The lands were at the time in the respective occupations of John Bacon, Thomas Rose and William Tickhill.

As must be evident in every reasoning mind, the rentals arising from these properties, added to the usual school pence, did not prove a fat living even for a bachelor and Mr. Hayes cast about for other occupation and shortly attached himself to Mr. Taylor, the Registrar for the District, for a time acting as deputy, until the death of that gentleman, then being elected in his stead, to the delight of the aspirant and the pleasure of those who recognised and appreciated his abilities. The increased labour consequent on this appointment did not exhaust the expeditious energies of the now important young man, who was destined very shortly to receive further honours, as vestry clerk for the parish and clerk to the Eckington Savings Bank – an institution promoted by a body of local gentleman termed Governors, with the Rev. C. B. Estcourt (Rector) as President. This bank was in existence for a number of years until postal facilities and easy access to towns rendered it unnecessary, as it was a friendly encouragement to depositors and not a beneficial speculation on the part of the Managers. In addition to the labours involved, Mr. Hayes being a competent surveyor was often encouraged in this capacity, also in preparing plans, agreements, indentures and apprenticeships, and the making of many wills – alert, industrious and experienced in all details of village life.

In school, the special feature was writing, of which art he was a most able exponent, the florid corresponding style of the 18th century. In addition to this writing, the education given was sound and useful, the other two Rs being carefully inculcated. If the master had taught grammar up to his own standard and in flourishes equal to his own penmanship, he would have said, “Almost everywhere we recognise a multiplicity of forms and tenses of the verb and an industrious artifice to indicate beforehand, either by inflection of the personal pronoun which form the termination of the verb, or by an intercalated suffix, the nature and relation of its object and its subject and to distinguish whether the object be animate or inanimate, of the masculine or feminine gender, simple or in complex numbers” the youths would probably have said it was ‘ripping’, if they said anything, but it would not help to make scythes and sickles.

It was always Mr. Hayes’ opinion that the working classes of the country villages were always better‑educated than the similar class and artisans in towns: school accommodation, resident gentleman who interested themselves in night and Sunday schools, the absence of places of amusement, the new facilities of getting to towns, all tended to induce the people to learn to read and write. He was greatly interested when the authorities in high places began to be concerned about the ignorance of the people generally and the dangers consequent thereon, prior to and after the Representation agitation and Bill of 1832 and was equally disappointed in the promised improvements being neglected when the masses were in effect reviving the cry, ”No Representation, no Musket” and were met with the reply, ”No Education, No Vote”, a very plausible, but very dangerous doctrine, nearly bringing the country into a state of revolution, following the example of France. The exposure of the sad ignorance of the workmen in Sheffield in 1852 reawakened the necessity of education, the charges then made attracted great attention in and beyond the borders of that town.

The Rev. Thomas Clarke, curate of St. George’s Church stated at a meeting of the Church of England Instruction Society, “that out of every ten mechanics of this town, seven would be unable to read or write legibly”. The accuracy of this statement was challenged by the grinders at Messrs Rogers’ Wheel, Norfolk Street, who held a meeting on the subject and proved that the remark did not apply to them as a body and passed a resolution to that effect, a copy of which was sent to the reverend gentleman. The subject of education was at that time creating much interest in Sheffield and the Press taking the matter up, additional interest was added, letters, leaders and semi-leaders followed for several weeks. Mr. Clarke proved by induction and inference that, although the statement might be inaccurate as applied to individual firms but in the aggregate, it was, in his opinion, unfortunately true. He received letters from other firms; one intelligent workman assured him that the statement, when applied to their branch of trade, would be found to be under the mark and that ten out of twelve could neither read nor write and added that in his branch numbering 300, not more than one in thirty ever went to school.

In Lodge’s’ Illustrated History of Britain’, an account was given of a seditious paper that was stuck up on St. Paul’s (London) Church in 1816 and in order to discover who had written it, the Aldermen and Privy Councillors were ordered by the King to go around all the wards and see who could write. Neither this nor any other satisfactory test could be made to apply to a town having a population of 130,000 inhabitants: there was one undeniable fact that, in the year 1845, out of 1,426 marriages in the Sheffield Registration district, 488 of the males and 790 females were unable to write their names and signed the register with their X and, if they were unable to write, the inference is that they could only read in such an imperfect manner as to be of little advantage or pleasure to them. The artisans were urged to rid themselves of the stigma by applying themselves to study and to practise writing more, especially as the Constitution, just then granted by her majesty in the Cape of Good Hope, required the elector, on giving his vote, to subscribe his name at full length, with signature to be attested by the officer taking the poll: thereby raising the possibility of Lord John Russell applying in his promised Reform Bill a similar condition and, if he did, what would become of manhood suffrage?

The following was one of the results in the place of Mr. Hayes’ birth – Worksop – the same year: –

On the occasion of an annual custom, Mr. Joseph Garside Jnr, the extensive timber merchant, and proprietor of the Prior’s Wells Saw Mills of Worksop gave a liberal and substantial dinner to his employees, 112 in number; after the usual loyal toasts, in proposing ‘improvement of the labouring classes’ Mr. Garside said he had resolved to establish a night school at his own works and paying a teacher to instruct those of his men who thought proper to attend and those of their children who were of a proper age and he would allow every person employed under him to leave his work at half past five, instead of 8 o’clock to attend their school. He should pay them their full amount of wages at the week’s end. Some of them had a taste for music and he was quite prepared to meet them in that department also. It was estimated that these concessions would cost Mr. Garside £250 a year in wages alone.

Mr. Hayes’ lived long enough to see the apathy in educational matters pass away and reach the other extreme, a fever height, when the department in all its branches and details ‘ran out of hand’ and became so flexible and obedient as though they could not expiate their former neglect in the days when he first appeared at Mosbro’, when the only other school was a dame school, kept by Mrs. Girby, when teachers were unenviable members of society, whose income was precarious and whose duties were many: he lived to see… Footnote 1

The many offices filled by Mr. Hayes’ necessarily took him a great deal from home: the district was long and broad and the roads very rough and lonely, which he had to traverse in performance of his duties. Many were the journeys impossible for wheels that had to be taken by saddle: flood and tempest did not prevent appointments being kept and there were other dangers of the road for which ‘hanging’ was the penalty: but from these molestations Mr. Hayes had exemption on being recognised. This freemasonry was also extended to the daughters of Mr. Hayes’, who were often deputy registrars, when their father had other appointments and could not perform dual duties: the roughest of the rough elements of the roads paid respect to Mr. Hayes and his representatives, for they knew the nature of the duties he or they were performing. The duties of registrar include the appointment of enumerators, the supervision of census taking and summarising the returns for his district: the first under his control being in the year 1841, when there were in Eckington parish 947 houses, 4,401 inhabitants, with an area of 6,610 acres: Stavely parish 2,668 inhabitants and an area of 6,290 acres: and Killamarsh parish 906 inhabitants and an area of 1,860 acres.

In vestry meetings, Mr. Hayes was often seen to advantage, the result of experience, tact and knowledge of facts and persons. These meetings at the time of his appointment as clerk, and for a number of years after, were very rural and uneventful. The statutory meetings for the appointment of church wardens and passing accounts at the Lady Day meeting for appointing parish officers – from the overseers of the poor to the ponder – being held without ‘accident’ until the population of Eckington and Mosbro’ greatly increased and with it the wear and tear of the roads and further demands for highway rates to which the outlying districts had to contribute, creating lively discontent. The Highway Board became of primary importance and the members elected with care and discretion, the quarters of the parish being represented by those most likely to secure the grinding of the particular axe of the neighbourhood, the Ridgeway quota insisting on the Carter and Bolehill Lanes, Renishaw-upon-Emmet Car Lane, Mosbro’-upon-Plumbley Lane (all occupation roads) being repaired by the parish: whilst Eckington refused to sanction any of them or, as an alternative, the local Harmsthorpe Road… Footnote 2

…thus, eventually the meetings were crowded out, almost at commencement, and adjournment had to be made in time in the Stag Room of the White Hart Inn. The rector who, ex-officio, was chairman in the vestry, as a rule deputed Mr. Charles Rotherham to fulfil the duties at the adjourned meeting: sometime the ratepayers disputed the authority of the deputy and wanted to appoint their own chairman at other times Mr. Joseph Wells or Mr. F. Barber officiated; there was generally a scene before the meeting terminated. Whoever presided, or whatever the object of the vestry, Mr. Hayes, like ‘Figaro’ in the opera, was always wanted and always there, stilling the tempest and restraining the verbal energies of the demonstrators. One gentleman (Mr. Septimus Staton – Footnote 3) to whom he paid close attention, was not a drawing room character; brusque, burly and assertive, and was generally to the fore; the rector might explain and appeal to others, the church warden might deny, refute and threaten, but the only soothing influence effective was the mild remarks of Mr. Hayes “who could be believed” and, by some suggestive compliment, Sep would get the best of the argument, but not of vote.

He also saw many changes in the Parish and district and his occupation brought him into contact with all classes of people. The collieries in his early days were comparatively few and limited in capacity; he saw them attain mighty proportions, promoted and owned in great part by his friends and neighbours. The Norwood Colliery of the Sheepbridge Coal and Iron Co. as also the several undertakings and extensions of the Stavely Iron Works were in his district. The Midland Railway became an actual fact, during the construction of which through the Killamarsh and Eckington meadows, he was repeatedly engaged as surveyor. The nights of teaching by double-wicked lights, the stages of the improved wax candles, the oil lamp, the introduction and success of gas, in the early days of the incandescent and electric light, Mr. Hayes experienced all these from the time when the streets of Mosbro’ and Eckington, with their yards and bye-roads, were alive with industries represented by the manufacture of sickles, hooks and scythes, mails (common and horse hammers, edge tools, adzes, spokes and shovels, chairs, tubs, dollies and other general goods, when a payment of 10/-to the poor rate represented ‘big works’, to the time when all these businesses were extinct save two survivors only, one at Mosbro’ (James Riley and Sons) and one at Eckington (Mr. F. Fanshawe). Mr. Hayes saw the workmen of Mosbro’ when they were infatuated by misleading outside dictators and also saw the employers of long years standing, and the mainstay of the village, being victimised and could only look on with profound sorrow and apprehension as shop after shop was being closed.

When the school and other official tasks were over, Mr. Hayes was most sociable and mingled freely with other residents in visiting and being visited and occasionally joined the social company of a number of staid convivial in the cosy smoke room of the ‘Crown Inn’, where the manufacturers and farmers mostly did congregate and enjoy a glass of gin with the usual accompaniment of a ‘churchwarden’ pipe of tobacco. This room was quite a forum, where matters political, parochial, local and especially the merits and demerits of Friendly Societies were discussed with interest and intelligence. At times, Mr. Hayes would reason beyond his depth or over the head of some of the company when expounding his ideas as to the origin of the scythe and its name in England; he claimed that it had more remote origin than any item of British manufacture and was anterior to the stone or bronze age and traced it to the ancient ‘Asiatics’ of whom the Scythians, so called from the name Scythia, given to a large portion of northern Asia were considered to have been the descendants of Gormer, the son of Iaphet, who practised the scalping of their enemy – a well-known custom amongst the tribes, supposed to be of the same race in America. The ancient Britons were of the same race of people. (The reasoning may be far-fetched and connection between the modern scythe, with its peaceful purpose with the ancient scalping knife of the Scythians and the noble ‘Red Indians’ of the ‘Wild West’ may appear improbable, but why impossible?) The schoolmaster may not be so ‘far abroad’ as some present-day sceptics would suggest; perhaps the Mosbro’ students of ancient history will solve the problem. (It would be an interesting research).

In later years, Mr. Hayes would occasionally be induced to speak of his early recollections, the cost of articles, limitation of taxation of articles of ornament, hats and gloves, modes and difficulties of travelling and anecdotes of the road with the more barbarous pleasures of that period. Mr. Hayes was always interesting and instructive at these impromptu meetings until, one by one, the associates Frederick Keeton, John Riley, George Mullings, Thomas Bunting, Joseph Alton, Luke Worrall, John Rose, John Staton and many others, younger than he, passed away, leaving him sole surviving of at one time a prosperous, happy band; the time however sped until on 9th July, 1890 (Footnote 4), 11 days short of his 90th birthday, this active and faithful gentleman peacefully exchanged a prolonged life for an immortality and there was no moaning at the bar. (Footnote 5)

Typed out from

“Proof copies of articles that appeared in the paper – presented by a descendant of Mr. Hayes”

Mike Hayes (a later descendant of Mr. Hayes!), April 20018

Footnotes

- I think a line or two has got cut off at the bottom of p5 of the script I copied from.

- The script had the words (this small portion of reading matter, 2 lines, is entirely obliterated by age and I have continued from there)

- Septimus Staton was an Ale house keeper at the “Butchers Arms”, now a hairdresser’s. Septimus’ father ran a local scythe and sickle works.(personal communication from Philip Staton)

- The script has 1900, but it says 1890 on his gravestone in Eckington churchyard.

- Crossing the Bar was a very contemporary poem, written by Alfred Tennyson in 1889!

The article makes presumably an intentional pun on the bar at The Crown that Mr. Hayes ‘occasionally joined’.

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea,

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;

For tho’ from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.

6. The article says almost nothing about his family life but again from the gravestone, his wife, Elizabeth was significantly older than him, dying on January 6, 1835, aged 55 years. The inscription says: Think what a wife, mother and friend should be, and she was that.

As well as the daughters referred to in the article, they had at least one son, also called John Ibbotson Hayes, who was indentured in 1850 to a silver engraver and printer in Sheffield.